This is the fifth article of a 10 part series on redistricting + apportionment + gerrymandering, in relation to Alabama.

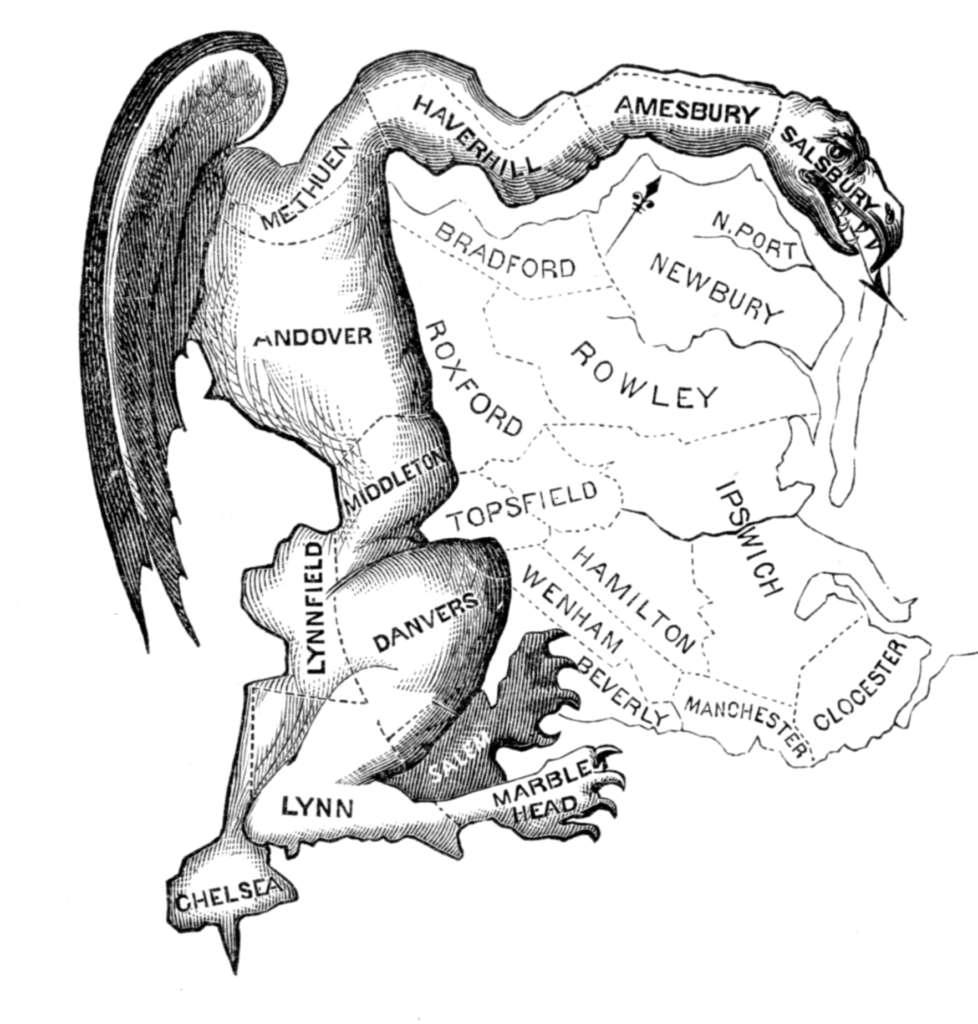

Let’s move back in time to 1812 (incidentally, the last time that we had a war with Britain), to Massachusetts, and to a local newspaper making fun of a politician. The politician was Elbridge Gerry (with the G pronounced like the g in “get”), who as governor signed a bill that created safe districts for his party. The newspaper drew a cartoon that showed that one absurd district looked like a salamander, and dubbed it “the Gerry-mander.”

Over time, we have decided to pronounce the word as if it were spelled “jerrymander,” but the manipulative political process has unfortunately endured. In the absence of clear and enforceable rules to guarantee fairness to voters, apparently the lust for power is too strong. Our Founders, of course, were aware of human frailty and designed our governmental framework with their best ideas in terms of “checks and balances” to help human beings maintain their moral compass, and to enforce the framework if there were violations. The redistricting process is, unfortunately, an area where we still lack clear and enforceable rules to guarantee fairness to voters.

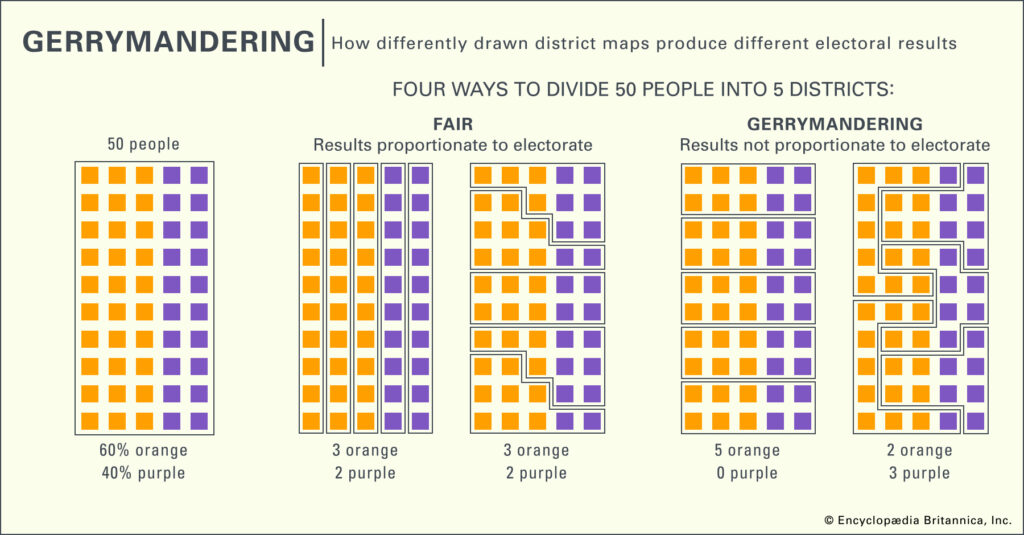

Remember that gerrymandering is a way that governing parties try to cement themselves in power by tilting the political map steeply in their favor. Also remember that this has been done by both parties. The goal is to draw boundaries of legislative districts so that as many seats as possible are likely to be won by the party’s candidates. Drafters accomplish it mainly through two practices commonly called “packing” and “cracking.” A packed district is drawn to include as many of the opposing party’s voters as possible. That helps the governing party win surrounding districts where the opposition’s strength has been diluted to create the packed district. Cracking does the opposite: it splits up clusters of opposition voters among several districts, so that they will be outnumbered in each district. An efficiently gerrymandered map has a maximum number of districts that each contain just enough governing-party supporters to let the party’s candidates win and hold the seat safely, even during “wave” elections when the opposition does especially well. And it packs the opposition’s supporters into a minimum number of districts that the opposition will win overwhelmingly. The concept is nicely illustrated in a diagram from the Encyclopedia Britannica that illustrates how to draw a map both fairly (in two ways) and unfairly via two gerrymandering approaches.

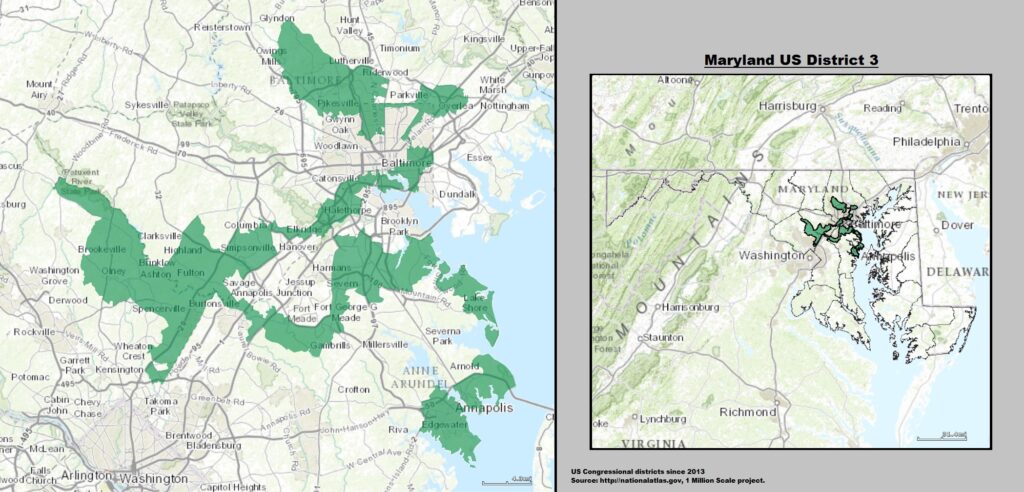

We began this post with the “salamander” example. Here is a more recent notorious Congressional district gerrymander, Maryland’s Third.

A solution? The current For the People Act (SB 1) is a way to create a federal framework to protect voters’ interests during redistricting. It requires Congressional redistricting be conducted through independent state commissions, with diverse membership and public notice and input. You can read the “redistricting reform” here (Title II Election Integrity, Subtitle E, Redistricting Reform). And here is a discussion of this section by the Brennan Center for Justice.

This series is a joint effort of the blog editor, Catherine Davies, and other members of the Advocacy Team and Board of the League of Women Voters of Alabama.