This is the sixth article of a 10 part series on redistricting + apportionment + gerrymandering, in relation to Alabama.

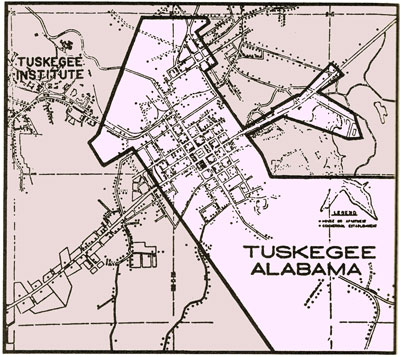

The good news here, and it involves a case from Alabama, is that RACIAL gerrymandering is not allowed. The case was Gomillion v. Lightfoot in 1960. In US Attorney General Garland’s recent memorable characterization in his address on voting rights on June 11, 2021, “the Supreme Court invalidated the infamous gerrymander of the city of Tuskegee, Alabama, which had redefined the city’s boundaries to exclude 99% of the city’s black population without removing a single white voter.” The Supreme Court threw out an Alabama state law that redrew the boundaries of the city of Tuskegee from the square of the map below, to the lighter-colored 28-sided figure which excluded all but 4 or 5 Blacks, while retaining all White residents.

Alabama was the site of Bloody Sunday in 1965, which galvanized Congress to enact the Voting Rights Act. Originally signed by President Johnson, the act was reauthorized and signed by President Nixon in 1970, by President Ford in 1975, by President Reagan in 1982, and by President Bush in 2006. Just as the Civil Rights Act of 1957 had reaffirmed judicial oversight of the political process by the Supreme Court, the 1965 act had a “preclearance requirement.” This meant that any changes to state-level voting processes, in places with a history of discriminatory practices, had to be reviewed and cleared (approved) by the DOJ before they could be put in place (that is, “preclearance”).

And that brings us to bad news from Alabama, in particular from Shelby County, Alabama, in a 2013 Supreme Court decision, Shelby County v. Holder (Eric Holder, the US Attorney General at the time). Apparently deciding that racism was no longer an issue in the United States, the Supreme Court decision “effectively eliminated the preclearance protections of the Voting Rights Act, which had been the department’s most effective tool to protect voting rights over the past half century.” This was a 5/4 decision, with Ginsburg writing the dissent. As League members, we are acutely aware of what has followed that decision in terms of state-level legislation promoted in the name of “election integrity” but clearly designed to restrict voting rights.

OK, you say, but what about the PARTISAN gerrymandering that we’ve been talking about? There’s more good Alabama news here: Another case from Alabama, Reynolds v. Sims in 1964, established the “one person one vote” principle. The Supreme Court held that the 14th Amendment “protects the right of each citizen to have an equally effective voice in the political process.”

But now for the bad news: In Rucho v. Common Cause in 2019, we get this decision from SCOTUS: “We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.” This was again a 5/4 decision, with Kagan writing the dissent. In other words, the Supreme Court will not involve itself in any cases involving partisan gerrymandering.

So it appears that we can count on the courts to protect us from attempts at racial gerrymandering, but not partisan gerrymandering. We do have a set of guidelines as of May 2021 for the Permanent Committee on Reapportionment. Given the fraught history of redistricting in Alabama, it’s up to us as citizens to be vigilant, helped by organizations dedicated to voting rights like the League of Women Voters.

This series is a joint effort of the blog editor, Catherine Davies, and other members of the Advocacy Team and Board of the League of Women Voters of Alabama.